Australia’s largest inland waterway

Gippsland Lakes, located in south-eastern Victoria, is made up of a series of shallow coastal lagoons and marsh environments that are separated from the sea by a barrier system of sand and dunes and fringed on the seaward side by the Ninety Mile Beach. Lake Wellington, Lake Victoria, Lake King are included in the system along with a number of smaller lagoons and wetlands, and flow into the ocean at Lakes Entrance through the permanent entrance that was established in 1989. The main lagoons and lakes are fed by river systems in a catchment of approximately 20,000 square kilometres or ten percent of Victoria’s land area.

The Lakes are fed with freshwater from five main rivers – the Latrobe and the Avon flow into Lake Wellington, the Mitchell, Nicholson, and Tambo into Lake King. The Lakes form the largest navigable network of inland waterways in Australia and contain a number of internationally significant wetlands and support a diverse range of flora and fauna.

There is evidence that the Gippsland region has been occupied by people for more than 24,000 years before European settlement. At the time settlement it was estimated that there were about 3,000 Aboriginal people from the Gunaikurnai clan living in Gippsland. Since then, the region has been explored, settled, farmed and used for a range of purposes.

The Gippsland Lakes are home to around 400 indigenous plant species and 300 native wildlife species and are internationally recognised as a feeding ground for migratory birds that travel from as far away as Siberia and the Arctic Circle. That is why this internationally renowned wetland is listed under the Ramsar Convention. The Lakes catchment is home to an abundance of wildlife that includes a wide range of threatened species, weeds and pest animals can place significant pressures on these threatened species as well as other common plants and wildlife, soil stability, waterways and agriculture.

The Gippsland Lakes is one of Victoria’s major environmental resources, an important tourism destination and home to people with a strong historical and cultural connection to the Lakes. Victoria’s largest fishing fleet also call the Lakes home, and supports tourism businesses an coastal settlements that provide lifestyle and visitor experiences including boating, recreational fishing, water sports and nature-based activities.

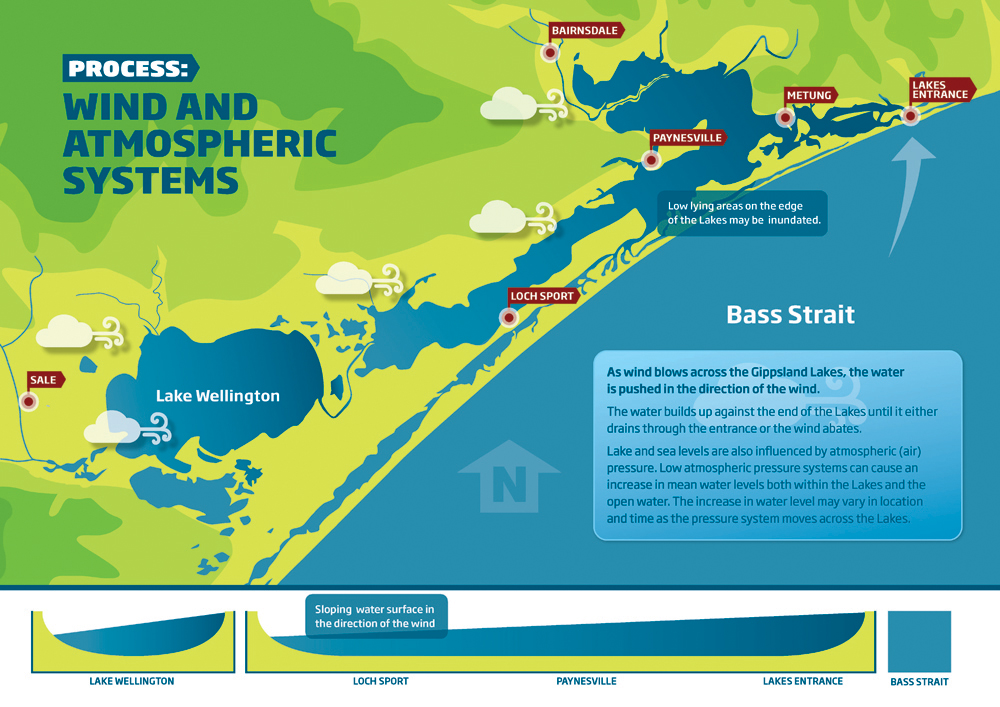

Wind and atmospheric systems

As wind blows across the Gippsland Lakes, the water is pushed in the direction of the wind. The water builds up against the end of the lakes until it either drains through the entrance or the wind abates.

Lake and sea levels are also influenced by atmospheric (air) pressure. Low atmospheric pressure systems can cause an increase in mean water levels both within the lakes and the open water. The increase in water level may vary in location and time as the pressure system moves across the lakes.

Over 500 million years in the making

About 500 million years ago, when plants first grew on land, most of Victoria was under a deep sea. Not long after, geologically speaking around 440 and 420 million years ago, a major period of mountain building took place and a lot of the Gippsland became dry land.

The Gippsland Lakes coastline that we know today has been shaped during the last million years and it is still continually changing (dynamic).

As the sea retreated, it deposited sandy barriers that now separate the Gippsland Lakes from the sea. Generally three barriers are recognised. The outer barrier lies on the south side of the Lakes, its seaward side is better known as the Ninety Mile Beach. An inner barrier lies north of Lake Reeve and a prior barrier forms the northern edge of the lakes system.

The barriers are kept largely in place by a cover of scrub, woodland and heath vegetation. Generally, these barriers are low in height, less than 10m above sea level. There are some exceptions where summits are higher than 30m.

Before the artificial entrance was cut, river floods would build up the level of the lakes until water spilt out across a low-lying section of the outer barrier. In dry weather, low river flow and high evaporation lowered the lake level and the outlet would become sealed by sand deposition.

Mitchell River Silt Jetties

Of international significance, the Mitchell River delta and its silt jetties is one of the finest examples of this type of landform in the world.

The silt jetties are formed by sediment deposits from the Mitchell River and persist due a lack of tidal currents in Lake King and the presence of a shoreline reeds fringe able to trap a large proportion of the river sediment whilst protecting the deposits from wave erosion.

Changes in vegetation over recent decades have resulted in erosion.

In-flows and out-flows

Before the artificial entrance was cut in 1889 river floods built up the level of the lakes until water spilled out across a low-lying section of the outer barrier. In dry weather low river flow and high evaporation lowered the lake level and the outlet would become sealed by sand deposition.

Spring tidal range at Lakes Entrance is about a metre, but tidal movements are not transmitted far into the lakes. Tidal influence at Metung for example is only about 10cm. The further west into the lakes system you go, the greater the water height is influenced by weather conditions rather than by tides.

After heavy rain and river flooding the level of the lakes rises and water pours out of the entrance, even against the incoming tide.

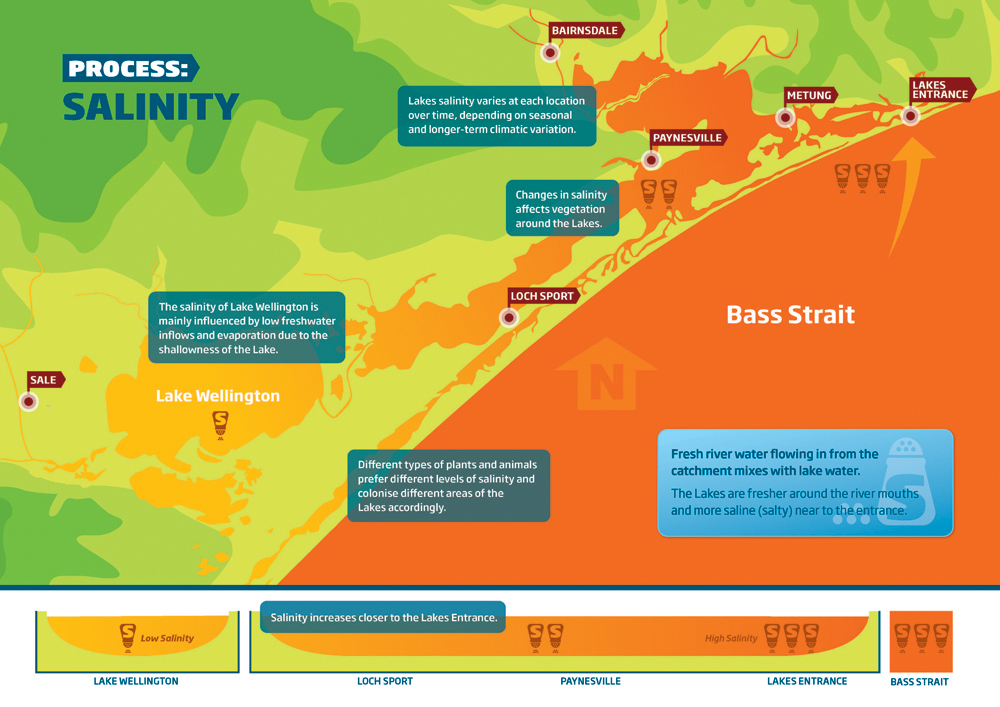

Salt loads in the lakes

Salinity conditions in the lakes are largely determined by the fresh water from rain and rivers flowing into the lakes and salt water flowing in from the sea.

Salinity at the surface of the lake is generally less than salinity at depth, particularly in calm weather.

In summer and autumn, when evaporation is high and fresh water input from rain and rivers reduced, the salinity of the Lakes increases. In winter when evaporation is low and rainfall higher the increasing river flow decreases the salinity of the Lakes.

The salinity of the Lakes has a big influence on the plants and animals that live in and around the lakes.

Wind and atmospheric systems

As wind blows across the Gippsland Lakes, the water is pushed in the direction of the wind. The water builds up against the end of the lakes until it either drains through the entrance or the wind abates.

Lake and sea levels are also influenced by atmospheric (air) pressure. Low atmospheric pressure systems can cause an increase in mean water levels both within the lakes and the open water. The increase in water level may vary in location and time as the pressure system moves across the lakes.

Algae is good in small doses

Algae are an essential part of a healthy Lakes system. Algae produce oxygen and are important food and habitat source for fish, water birds and invertebrates.

A diverse group of plants, algae are mostly microscopic. In low numbers they are not highly visible and are an important part of the food web. We generally see algae as ‘algal blooms’, which are made up of millions of algae. A bloom may suddenly appear as a thick, smelly, green, paint-like scum on the surface of a river, lake or dam. Blooms appear quickly as algae are capable of dividing and doubling in number every 2 or 3 days.

Algal blooms – their causes and impacts

Algal blooms can cause problems. They can look unattractive, smell horrible and make the water taste unpleasant. Also some species produce toxins which, following contact, can cause skin irritation, diarrhoea and vomiting as well as other more serious side effects.

When an algal bloom dies, the decaying algal cells use up the available oxygen in the water causing oxygen depletion, which can result in fish kills.

Reduce the bloom and look after the Lakes

Some of the main factors that contribute to algal growth are abundant nutrients, warm weather and relatively still, calm conditions. Limiting the nutrients entering our waterways and Lakes may assist in controlling algal growth. Protecting and revegetating our lake foreshore and riverbanks is one way to help minimise algal blooms.

Algae, fish, birds, dolphins, humans – we all rely on water quality.

In this video, Sean Phillipson talks about the role of algae in the Gippsland Lakes system.

The Victorian Environmental Protection Authority currently undertakes monitoring in three of Victoria’s major embayments:

- Port Phillip Bay

- Westernport Bay

- Gippsland Lakes

Monitoring is undertaken at 16 sites on a monthly basis for nutrient and algae levels, oxygen conditions and water clarity, which can have a negative effect on marine systems.

Water quality assessments are completed by the Ramsar Site Coordinator – East Gippsland CMA, as part of the commitments of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan and are reported on in the Gippsland Lakes Environment Report.

For details about monitoring results, check out the Victorian Water Measurement Information System.

Rivers, lakes and lagoons

The Gippsland Lakes are made up of a series of shallow coastal lagoons separated from the sea by broad sandy barriers. They include Lake Wellington (138 square kilometres) Lake Victoria (110 square kilometres), Lake King (92 square kilometres) and a number of smaller lagoons and wetlands.

Five main rivers drain into the Lakes: the Latrobe and the Avon flow into Lake Wellington, the Mitchell, Nicholson, and Tambo into Lake King. The total catchment is more than 20,000 square kilometres.

The Lakes are generally shallow; much of Lake Wellington is less than four metres and much of Lake King less than six metres. Lake Victoria occupies a long narrow furrow up to ten metres deep. The deepest point in the Gippsland Lakes is approximately fifteen metres near Shaving Point, Metung.

Ecosystems

The Lakes catchment includes a large diversity of land types each with its own plant community. There has also been a variety of man-made changes to the vegetation. The main factors that determine where vegetation grows are rainfall, temperature and soil fertility.

Within the catchment

Vegetation ranges from relatively natural native forests, woodlands, heaths and grasslands, through to highly modified and managed vegetation such as pastures, crops and pine plantations.

Forests and woodlands

Forests and woodlands within the Gippsland Lakes catchment vary considerably with elevation. Snow-gum woodland is found in the sub-alpine areas. Moving down the forest changes to stands of alpine ash, then mountain ash and mixed eucalypt forest. On the coastal plain there are still areas of open grassy Red-gum woodland.

Scrub and grasslands

Along the coastal beaches tussock grasses persist, giving way to coastal tea-tree scrub on more sheltered sites. There are also areas of banksia woodland and swamp paperbark.

Around Lake margins

Fringing wetlands around the Gippsland Lakes include areas of freshwater and brackish wetlands as well as areas of saltmarsh. These areas are vegetated with a wide range of plants.

Within the Lakes

Within the Lakes there are areas of seagrass, important for fish breeding. As well there are open lagoons that tend to have a presence of algae. They may be quite saline, such as parts of Lake King, or brackish like Lake Wellington.

The Lakes’ superpower

Seagrass is the powerhouse of the Gippsland Lakes ecosystem. It provides valuable habitat for fish and invertebrates, as well as stabilising the lake bed. Seagrass also provides food for fish and birds. Some birds, like swans, eat the seagrass but most fish and birds rely on eating the bugs that are eating the seagrass.

Three species grow in the Lakes, generally in depths less than four metres due where there is enough sunlight for growth. In the deeper areas you will see Zostera nigricaulis and Ruppia spiralis, sometimes growing together. Zostera mulleri grows in shallower areas where the seagrass may be exposed by tidal movement of the water.

Parks Victoria have a very informative guide available to assist in identifying seagrass.

Top tips for helping to protect seagrass in the Gippsland Lakes

Be aware

If you live near the coast or along a river, reduce your use of fertilisers and pesticides on lawns and farms.

Know your boating signs

This will prevent you running aground and damaging seagrass beds (and potentially your boat)

Know your depth and draft

When in doubt about the depth, slow down and idle. If your are leaving a muddy trail you are probably cutting seagrass.

Be on the lookout

Be aware of your surroundings and look out ahead. This also helps protect marine animals (and your passengers).

Study your charts

Use navigational charts, fishing maps, or local boating guides to become familiar with waterways.

Wildlife wonderland

The Gippsland Lakes are home to around 400 indigenous plant species and 300 native wildlife species. Some of these species are listed as threatened, such as the dwarf kerrawang, metallic sun orchid, swamp everlasting, growling grass frog, spotted-tailed quoll and the wandering albatross. The presence of these plants is one of the reasons the Gippsland Lakes was nominated as a Ramsar site.

Fish

A range of fish species live in the Gippsland Lakes. Generally, fish spend their juvenile stages in shallow waters, particularly around seagrass. Most adults have more flexible requirements and occur across a range of the available habitat types. Common species include black bream, mullet, dusky flathead and tailor.

Black Bream

Black Bream are an important fish of the Gippsland Lakes. Although they live in estuarine and freshwater conditions they require salinities of 11,000 – 18,000 ppm (about half the salinity of seawater) for spawning to occur. It takes over 9 years for a Black Bream to reach the minimum legal limit of 28cm.

Birds

Waterbird abundance and diversity is one of the most important aspects of the Gippsland Lakes. The Lakes provide important feeding, resting and breeding habitat for 86 waterbird species, many of which are listed under international conservation agreements. The Lakes are home to a significant pelican rookery.

The most popular areas of the Lakes for waterbirds are fringing wetlands such as Dowd Morass, Heart Morass and Sale Common as well as the salt marshes and saline wetlands such as Lake Reeve.

Migratory birds that enjoy our Australian summer include snipe, sandpipers and terns whilst birds that winter here include the cattle egret and double banded dotterel.

Frogs

The Lakes are home to two threatened frog species: the green and golden bell frog and the growling grass frog. These two species are capable of hybridizing and there are areas around the Lakes where the species and the hybrids co-occur.

Growling Grass Frog

The Growling Grass Frog (Litoria raniformis) is one of Victoria’s most endangered frogs.

Adult males have a very distinctive call that is described as ‘a long modulated growl or drone, followed by a few short grunts: crawark-crawark-crawark-crok-crok’. The Growling Grass Frog is reported as eating a wide range of prey including insects, small lizards, fish, tadpoles and even other frogs. It is a ‘sit-and-wait’ predator.

Growling Grass Frogs need still or slow moving water, ideally with lots of different water plants. They enjoy the fringing wetlands around Lake Wellington but can also live in farm dams and irrigation channels.

Mammals

The Lakes are home to a range of mammals, that live both in the water and on the land. One of the most notable marine mammals is the Burrunan dolphin, which is endemic to the Lakes and Port Phillip Bay.

A land based mammal that is popular with locals and tourists, are the koalas that live on Raymond Island, just off Paynesville.

There are also those species that live both on the land and in the water like the platypus, which can be found in the freshwater rivers of the Lakes catchment, and the often-misidentified native water-rat.

Water-rats (aka Rakali)

Australian native water-rats, also known as rakali, live in and around the Gippsland Lakes. These small attractive mammals in many ways resemble a small otter. Competent swimmers they have a thick, furry tail that acts as a rudder and webbed hind feet to assist paddling.

Water-rats often choose a favourite, scenic spot to eat. If you have noticed a large pile of fish bones and scales it’s probably the remains of a water-rat feast.

The rakali is one of Australia’s least studied mammals. A new project is now asking for help to record sightings. More information can be found at: http://www.platypus.asn.au/

More resources

Many apps and guides are available for you to further explore the Gippsland Lakes and surrounds, we have listed some below:

- Gippsland Lakes Wildlife Guide

- Museum Victoria – Wildlife Field Guide app to Gippsland Lakes

- Learn more about what it means to be a citizen scientist.